![]()

EMU - Gambling with Europe's Economies

![]()

| The case for EMU is well known, but is usually long on rhetoric

and short on detail. Jon Ralls spoke to Professor Andrew Hughes-Hallett of

Strathclyde University, and found out why.

(INTERNATIONAL FUND STRATEGIES, March

1997 |

|

|---|

![]()

"The political debate has been allowed to polarise ... it is hard to explain being pro-Europe but anti-EMU. "

Until very recently, and certainly since the Maastricht Treaty, monetary union seemed to have become a foregone conclusion - politicians and economists talked as if it were going to happen and it was time to focus on the details of convergence, and who might or might not join and when. Now, at the eleventh hour, serious questions are being asked about the wisdom of going ahead at all, especially given grass-roots opposition in Germany and France which have been EMU's most vocal proponents.

The unholy political alliance that puts the 'anti' case is muddled and, at its most shrill and xenophobic, is irrational and alarming. The European establishment, in turn, does itself a disservice by failing to inform the general public and, allegedly, closing down discussion on aspects of the debate that do not suit its political objectives. The politics and economics are inextricably linked, and reducing the argument to a Euro-philes versus Euro-phobes slanging match has caused a great many intelligent and influential people to take sides without really understanding the implications of proceeding, or not proceeding with monetary union.

Most of the reasoned debate has therefore been about implementation, meeting convergence criteria etc., without answering three more fundamental questions:

Some elements of the arguments for and against the principle of EMU (and its currently proposed form) are used in debate, but often in a confused and contradictory way. One reason for this may be found in the oft-repeated phrase that EMU is not about economics, it is about politics. However, as Eddie George, the Governor of the Bank of England, points out, it is a political decision with major economic implications. Since economic policy (fairly narrowly defined) currently occupies a central role in politics, the economic arguments and their implications for people, industry and the financial sector across Europe are of great importance. And, equally important, the question "What's in it for us?" begs a fourth question about who might benefit and who might bear the costs.

Eddie George, speaking in Milan last year, summarised the case for economic integration, as a sub-case of the arguments for competition and free trade: "The removal of barriers to international trade increases the scope for competition between producers of tradable goods and services. Increased competition increases aggregate economic welfare within the free trade area through benefits to consumers and as productive resources are redeployed to take advantage of comparative efficiencies and economies of scale."

Extending this to monetary integration and union, he continued: "You do not actually need monetary integration within Europe to derive substantial benefits ... The question is how far (it) can increase the benefits of the single market, and at what cost ..." Further: " Monetary union would represent a very much more powerful discipline on the participating economies ... there would be no possible escape route through exchange rate depreciation from undisciplined wage or price behaviour, which would then tend to result directly in falling activity and rising unemployment in those parts of the euro area in which they occured. To this extent monetary union would provide greater assurance of macroeconomic stability, as well as removing permanently uncertainty about nominal intra-European exchange rates as a factor in investment decisions by the financial and business communities."

But if exchange rates are such a problem, why do we have them at all? The economic theory behind them (and the implications of giving them up) is not as complicated as it appears. An exchange rate is a price like any other, reflecting a nation's net worth compared with its trading partners. Thus, if a nation's goods (exports) are in excess supply, the price (nominal exchange rate) will fall, allowing quick and simple adjustment for differences in aggregate supply and demand between countries, bringing them back into equilibrium.

Again at a simple theoretical level, if exchange rates are removed, any disequilibrium in trade must result in adjustments somewhere else. If the average price of traded goods cannot move, the individual prices of the goods themselves must change - a much slower and more complex process. There are two particularly striking consequences of this, one obvious, one less so. Firstly, if prices fall, so do profits and, eventually, so must costs, whether by cutting wages, employment, capital investment or whatever. Secondly, all that is required is that average trade-related prices move - some prices might move much more than others to achieve the overall adjustment.

In the real world, this process can be both inequitable and highly inefficient. To achieve the required average change in overall price levels, certain sectors will bear the brunt of the adjustment, as a direct result of the stickiness of prices in others. The most obvious example is the labour market, where those in weaker sectors would suffer much greater falls in prices (lower wages) and quantities (unemployment), and take the fall for those with more bargaining power and those on fixed incomes, such as pensions or annuities.

|

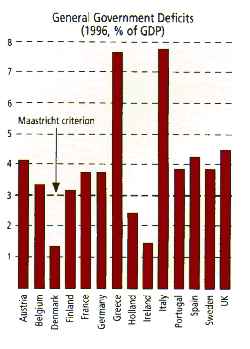

Professor Andrew Hughes-Hallett, Professor of Macroeconomics at Strathclyde University, points out that this bears an uncanny resemblance to what is happening across Europe as countries have partially given up the exchange rate tool and struggle to meet the convergence criteria. "Europe is one of the clearest examples of a region with sticky prices due to regulatory mechanisms and perceptions that prices/wages do not fall, and it is therefore taking the hit in quantity terms, hence high and rising unemployment. The only three exceptions are those that have had to bite the bullet, very painfully, and force wage flexibility - the UK, Ireland and The Netherlands." (See below).

Chris Godwin of IBM, contributing to an Internet debate on Britain and EMU, wrote that monetary union is "yesterday's future" - he was largely referring to the ambitions of elderly politicians, but this view is also supported by Hughes-Hallett's economic argument: "The logic that devaluations lead inevitably to inflation comes from the era of full-employment, when politicians acted inappropriately." In situations of full employment and capacity shortage, devaluation to redress a trade deficit results in an increase in demand which cannot be met, prices rise, wages rise in response, and the result is inflation. "If instead there is excess capacity, as in the UK when it dropped out of the ERM in 1992, a devaluation can work. In this case, the expected rise in inflation did not happen - exactly as predicted by broader economic models." The myth is not based on 'sound economic theory', but on the experience of frequent misuse of devaluation as a soft option.

As an aside, this still leaves the problem of 'competitive devaluation' but this is not a problem with the instrument, it is again a problem of its abuse. Governments do not combat unfair price competition by fixing prices but through competition policy. To argue that competititve devaluation should be prevented by doing away with currencies is as one-sided as suggesting the same solution for excessive currency speculation - again, the problem there may not be the currencies but the speculation.

To return to the main argument, exchange rates exist and fluctuate to maintain equilibria between national economies. The costs of failing to get and keep the parities right are collosal - think, for example, of the costs to the whole of Europe of the Deutschmark's movements in the early 1990s (related to German unification) dragging the other ERM countries nominal exchange rates out of line with the real economy. Since the 'right' parities are not necessarily constant, something has to give - as shown above, in the absence of exchange rates, falling wages and unemployment are the most likely outcome.

|

This is where the costs of EMU first appear - in cold economics, poverty and unemployment are not just about human misery, they are also extremely expensive, being about huge fiscal deficits and, thereby, they threaten the stability of the Euro. While there could be greater stability within the European financial markets as a result of EMU, it is increasingly clear that the Euro will be nothing like as strong as the Deutschmark and could be more volatile against (say) the U.S. dollar than a basket of the existing European currencies. This could happen through any (or a combination) of three mechanisms:

Thus, for global institutions, the advantages of greater financial stability within Europe may be offset by increased volatility and uncertainty surrounding the Euro in world markets. But, in the absence of adequate counter-measures, the initially greater financial stability within Europe may itself bring about some of the structural changes in (2) above - for which, as Charles Dallara, formerly an executive director of the IMF, has pointed out, the Maastricht criteria make no allowance.

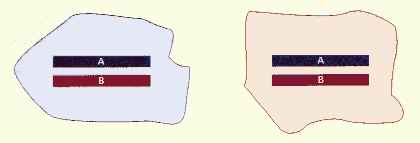

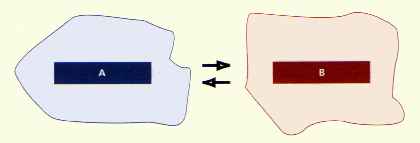

At the heart of the argument for the single European market is the idea that, by doing away with barriers of all kinds - barriers to trade, and to movements of capital and labour - specialisation on a Europe-wide level can realise greater economies of scale than are possible within individual countries. This could have benefits both in terms of economic efficiency, and by creating companies large enough to compete with American and Asian transnationals. This outcome is shown in Scenario 2 on the diagram. If barriers such as tariffs, exchange and political risk, and labour cost differentials are removed, this is the 'efficient' outcome towards which industries will tend.

| TRADE

AND SPECIALISATION TWO COUNTRIES, TWO INDUSTRIES |

|

|---|---|

| COUNTRY ONE | COUNTRY TWO |

|

|

| SCENARIO 1:

BARRIERS Barriers result in negligible trade. Countries One and Two are each basically self-sufficient, each with both industries, fully vertically integrated. Two entirely separate markets. |

|

|

|

| SCENARIO 2: NO

BARRIERS No barriers to trade, capital or labour movements. Country One has a comparative advantage in industry A, and Country Two in industry B. In this extreme example, each has specialised entirely, and produces for both markets, trading exclusively in finished goods. provided all costs are reflected in prices, this is the most economically 'efficient' outcome. |

|

|

|

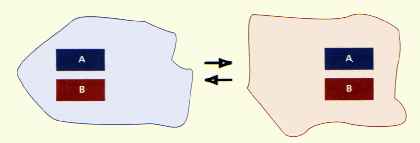

| SCENARIO 3: SOME

BARRIERS Partial implmentation of single market. If capital can move freely but labour movements and costs are 'sticky', industries relocate parts of the production process according to regional differences. 'Second best' strategy by each industry results in competitive 'dumping', large external costs, and adverse distributional effects. |

|

But Europe is not and cannot be, for the forseeable future, a barrier-free single market. The lack of cultural, linguistic and economic homogeneity between countries and even regions within them creates a serious imbalance in the labour market, spilling across to generate unstable investment conditions, which meeting the Maastricht convergence criteria in full cannot resolve. Apparently eliminating risk, one of the last barriers to free movement of capital, in a situation where labour cannot possibly move as freely, can easily have the effect of splitting up production processes. More companies will relocate the labour-intensive stages of production or service provision to areas with low labour costs, exacerbating the regional assymmetries referred to above (see diagram Scenario 3). There will be more cost competition to attract capital, through reduction of wage and non-wage costs of employment (known as 'social dumping') and tax breaks (known as 'fiscal dumping').

Corporations, including major financial groups, will rationally pursue such a 'second best' policy to maximise profits but, while the overall average level of economic activity may rise, the distributional effects are potentially catastrophic. Regulatory measures to reduce this effect, such as the Social Chapter, will be under enormous pressure and could never be strong enough. European corporations will continue to merge and grow to emulate non-EU corporations, but the lack of vertical integration will impose additional costs that will affect their competitiveness and continue to drive them to locate divisions in still lower-wage countries elsewhere in the world.

Differences in prices and costs between countries/regions are effectively the 'real' exchange rate between them. The adverse distributional effect is at least partly counteracted if the nominal exchange rate movements can move into line. In the absence of exchange rates, there are still other options, but each has its own problems:

A cynic might suggest that proponents of EMU within the European Commission are well aware of the fiscal implications of monetary union but, if they are, they are playing out a hugely risky political power game. To see the scale of the problem more clearly, let us look at an existing monetary union, the U.S.A. There is far more homogeneity across this huge area, in terms of culture, language, legal structures etc., than is ever likely in Europe, and there is greater labour mobility and wage flexibility - that is why the U.S. monetary union has lasted this long - that and redistribution on a massive scale. The federal budget represents the lion's share of all fiscal movements, some 25% of GNP, by comparison with which the taxes raised by individual states are tiny. Thus, if the Texan economy were to slump, the rest of the U.S. would absorb the reduction in tax revenue raised, and the increases in social expenditure in the state.

Europe has nothing equivalent to this in its proposals for EMU - the EU structural funds are only 1% of GNP - yet it is proving hard to persuade European electorates to support those on low incomes within their own borders, let alone finance geographic redistribution on the scale that occurs within the U.S. Indeed, the U.S. government is finding its own system politically harder to maintain. Yet, as we have seen, flows of capital to where costs can be externalised will, in the absence of exchange rates, perpetuate and exacerbate these distributional effects.

Without Europe-wide redistributive fiscal mechanisms, the almost inevitable result of doing away with exchange rates and this competitive cost-cutting, will be to generate huge national fiscal burdens. Cuts in health, social security etc. have proved easier to sell to electorates than a fall in weekly or monthly pay packets, but the long-term costs of such cuts is beginning to show up. Despite such measures, many countries are still finding it hard to meet the deficit targets, and and we (the financial sector) continue to punish (through the financial markets) those countries which run up large deficits - taxes will have to rise.

In summary, much of the 'pro' argument centres around the projections of a substantial rise in average financial income and wealth as a result of EMU. It is also likely that the financial sector would reap a substantial share of that rise. However, the costs are huge and there are no mechanisms in place to deal with the distributional effects, in particular the lack of a coherent fiscal policy to cope with assymmetries that are long-term and structural. Leaving these problems until later is a bit like investing in plant without calculating the cash-flow implications. Further, given that the predicted 1.5% sustained once-off increase in European GDP is well within the error margins of macroeconomic models, there is a serious risk of incurring the costs and getting none of the benefits - in trying to 'cure' instability and uncertainty, it may end up creating far more. The long term and unhedgeable risks that could arise from this scenario would make the costs of coping with exchange risk pale into insignificance.

The xenophobes do the case against a great disservice - there are rational, pro-European arguments against EMU. Even leaving aside arguments about the principle of EMU, there are undeniably serious gaps in the existing plans. On the present terms of debate, whoever wins the financial sector may lose out since, either way, the wider cause of European integration will not be served. To quote Martin Kettle, political columnist: "Even those who would like the single currency to succeed in the future ought to hope that it does not come about now." Not only is the present design is fundamentally flawed, but sufficient convergence with its limited criteria cannot be achieved without fiddling the figures to an extent that will throw up massive disequilibria at a later date. Kettle describes this as "the budgetary equivalent of crash-dieting." Italy is even introducing a one-off tax, to help it meet the criteria, which is to be repaid to tax-payers after EMU qualification.

Resolving the fiscal question appears to be politically impossible at present, which may be why the political debate has been allowed to polarise. There has been a great deal of rhetoric about cohesion and growth, but not much analysis of fundamentals - which is why it is hard to explain being pro-Europe but anti-EMU! But for the financial sector and asset managers in particular, there is a more direct threat than the risks of a weak and volatile Euro, or of nebulous 'fiscal imbalances' and political instability. Bluntly, EMU as currently planned means higher taxes which, ultimately, means lower corporate profits, hitting fund managers where it hurts. The best that can be hoped for is an eleventh-hour debate on the real issues, that will either bite the bullet on fiscal policy or at least postpone monetary union until the risk-adjusted return looks a little less terrifying.

Jon Ralls, February 1997

(c) 1997, Centaur Communications Ltd

![]()

Jon Ralls and International Fund Strategies are grateful to those who contributed ideas and contacts. Comments or requests for further information are welcome by email.

![]()

• Top of Page • Back to IFS Intro • Home •