![]()

'Development' in Asia - Miracles, Myths and Mirages

![]()

| Jon Ralls analyses development trends in Asia and canvasses the

views of three emerging market gurus: Michael Howell, Antoine van Agtmael, and

Mark Mobius

(INTERNATIONAL FUND STRATEGIES, December

1996 |

|

|---|

![]()

"Investors will not look for a further 'big bang' in deregulation, but for policy consistency... if they see a macroeconomic imbalance develop... it's punished, in the exchange rate and in the stock market" -

Antoine van Agtmael

![]()

Asia has, for many years, been a pot of gold for foreign investors, be they colonial traders, transnational corporations or, more latterly, portfolio investors in these 'emerging markets'. At a recent lecture in Edinburgh, Michael Jacobs of the London School of Economics pointed out that the region has now largely escaped from the degree of financial dependency still suffered by many of the peoples of Latin America and Africa. From raw natural resources to cheap manufactures to sophisticated technology, the loop is frequently closed completely and profits alone are exported - in Singapore recent estimates suggested some 28% of GDP went in transnational profits alone.

But what is generating these profits? In macroeconomic terms, investment returns have come from the extraordinary growth in GDP in 'emerging markets' - a process of very rapid industrialisation and growth in value of trade of which the Asian 'Tiger' economies are held up a paradigm. But who is gaining and losing (and what) in the startling transformation of country after country? Will investors continue to profit from this process and what might be the determining factors? Some of the answers may not be as obvious as they seem.

On the 20th January 1949, President Harry Truman launched the development era when, in his inaugural speech, he referred to the poorer parts of the world as "underdeveloped areas". The term was not entirely new - Keynes referred to "less developed countries" during the Bretton Woods negotiations in 1944, and the concepts underlying it had much deeper roots in the economic liberalism of nineteenth century colonialism - but Truman placed it fairly and squarely on the international political agenda.

The coining of the term embodied and legitimised certain key and closely related assumptions to which we shall return. For better or worse, it represents not just an economic framework but a political ideology. Discussing the rise of 'developmentalism', Bill Adams of Cambridge University quotes Chilcote's description of development seen as "a linear path towards modernisation" and notes how this perspective that "progress down that path could be measured in terms of the growth of the economy, or some economic abstraction such as per capita GDP."

The World Bank switched its stated focus in 1973 from the provision of infrastructure to an explicit aim to eradicate absolute poverty. This was translated into a massive push to initiate more projects and lend more money - in the process giving the green light to others to join the lending spiral that led to the debt crisis, rescheduling, 'Structural Adjustment' etc. that are still crippling a great many nations today. Much of Asia, however, having largely escaped from this degree of financial dependency, has a different set of problems.

| Some myths about 'development' in Asia |

|---|

|

Enter 'portfolio investment' - in common with corporate libertarian thinking the world over, corporations and economists are now successfully pushing a slightly different development model. Growth and liberalisation of capital markets are to encourage both foreign portfolio investment and the repatriation and expansion of domestic capital, promoting a more 'efficient' and dynamic 'entrepreneurial development', eventually completing the universal transition to capitalist free-market economies.

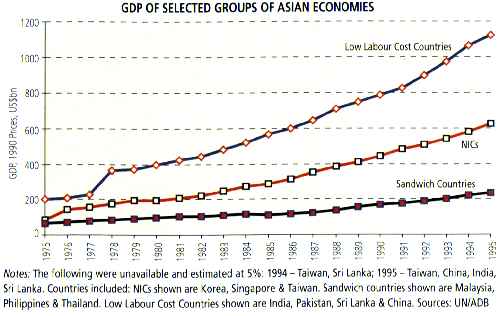

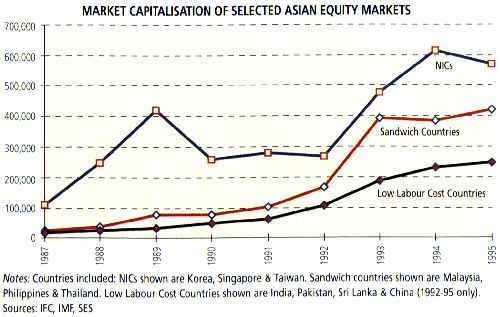

World Bank figures show that although "portfolio flows [into developing countries], especially equity flows, declined during 1994 and 1995, reflecting their greater susceptibility to short-term shocks and changes in market conditions ... portfolio bond and equity flows have both recovered strongly in 1996, contributing to a further increase in private capital flows this year." The temporary decline can be seen in the levelling off of the graph, showing market capitalisations of selected Asian markets (aggregated into categories suggested by Dr Mark Mobius of Templeton - see below).

The deregulation and liberalisation of capital markets is essential to this new phase of the development of capitalism in the region, and those promoting it are engaging in a degree of historical revisionism which is in danger of blinding many people to the true nature of the Asian 'miracle'. The old interventionist ideology has delivered spectacular economic growth but at enormous human and environmental cost. Since the case supporting the new ideology's promises, based on surrender to the 'invisible hand', seems to rest on re-writing history, it seems appropriate to question its assumptions and objectives.

The following interviews give us the views of three of the leading Asian / 'emerging' market specialists in the investment management community. They are of particular interest, both for the differences in specifics and for the basic similarity of their models. This is illustrated most clearly in their different understandings of 'sustainable development' - differing in detail, but all interpreting it as fundamentally an economic concept.

![]()

![]()

The interviews: print copy includes interviews with:

![]()

![]()

"Again and again ... degradation in the wake of development was redefined as a lack which called for yet another strategy of development." (Susan George, Transnational Institute) When 'development' is finally de-linked from 'growth', investment fundamentals will change beyond recognition.

![]()

"The outlook for portfolio investment in the region is excellent" - all three men agree. Their predictions vary somewhat in detail, but carry a number of common threads:

The standard assumptions of mainstream economics implicit in the analyses of all three, lead to a particular and familiar line of argument, so broadly accepted that it is rarely stated. (It also underlies many World Bank publications despite the apparent shift in its position.) Somewhat simplified for clarity, some key threads (and there are many more) are:

Challenging these views is generally regarded as heresy, but seeing the theoretical and observable flaws in the current model can throw a different light on development in general and Asian development (as the supposed paradigm to emulate) in particular.

Looking first at a theoretical macroeconomic level, there is the fundamental problem that sustainable growth is an oxymoron. Herman Daly, former Senior Economist at the Environmental Department of the World Bank, shows that there cannot be infinite growth in real terms, since we live in a finite ecosystem. Drawing parallels with "traveling faster than the speed of light ... [or] building a perpetual motion machine", he speaks of the way that in science "by respecting impossibility theorems we avoid wasting resources on projects that are bound to fail." Like the perpetual motion machine, the only 'solution' is to cheat, in this case by continuously adding into the system scarce resources previously assumed to be infinite, effectively violating the definition of income, of which GDP is supposed to be a measure.

Growth and development need not be equated, for they mean very different things. Daly quotes dictionary definitions of the two: "To grow means 'to increase naturally in size by the addition of material through assimilation or accretion.' To develop means "to expand or realize the potentials of; to bring gradually to a fuller, greater or better state.' When something grows it gets bigger. When something develops it gets different."

Secondly, there is the narrowing of efficiency to imply 'profit maximisation' and 'global competitiveness'. Asia has been hugely efficient at this, at the cost of misallocations of resources through externalities on a huge scale. The most obvious example is that of fossil fuel use. The externalities are well-known - the many costs of air pollution, none of which are accounted for in the price. The industrialisation model of development arises from a calculation of 'efficiency' in which external costs such as destruction of environmental and social capital are irrelevant unless and until they have a direct effect through the market. The historical reality is that growth in Asia has occurred fastest in nations which combine low wages, low levels of protective regulation, and suppression of dissent.

Global competitiveness is all about externalising costs and thereby gaining at the expense of others, within or without national borders. This process can easily be traced through the colonial era and the FDI of foreign transnationals; now the more 'developed' Asian nations are, in turn, visiting the same treatment on their poorer neighbours. Professor Andrew Hughes Hallett, a macroeconomist at Strathclyde University in Scotland, believes that universal 'catching up development' is a theoretical possibility, but believes that the pain involved, especially in terms of vast disparities in income, may be so great as to be politically very uncomfortable.

The principal market for luxury manufactures and specialist financial services is roughly equivalent to the 8% or so of world's population owning a car - a very much smaller percentage outside the industrialised world. Concentrating on catering to this market is highly profitable in the short term, through strategies based on industrialisation and consumption-driven economic growth. Nowhere more so than in Asia, where the concentration of wealth and consumption are legendary and highly visible.

Professor Hughes Hallett has recently returned from Vietnam, where he observed: "GNP levels per capita are extremely low but, under a socialist regime, income distribution has been relatively even - what resources they had were spread pretty evenly. Now, the growth rate around Ho Chi Minh City is perhaps 30%, around Hanoi about 15% but, for the country as a whole, about 8%. That leaves the countryside, with some 70% of the population, stagnant."

The Vietnam government recognises that this trade-off is necessary to allow economic growth - as Hughes-Hallett said, "the main investors coming in are Western - you either compromise with them or you don't have the money". The government remains extremely concerned about the extent of the disparities and their implications; nonetheless, BMW and Mercedes already feel confident enough to have set up assembly plants for the domestic market!

He shares a related worry with the government - one which illustrates very clearly the consumption dynamic of the free-market approach to development: "... some of the financiers coming in now are not so interested in setting up production facilities, with all the employment and diversification implications of that, but instead see 80 million people they can sell things to ... it provides them with lots of jeans and Coca-Cola but not a sustainable income. The irony is that the Americans wasted a lot of time bombing the place flat in the 1970s - a strategy of just selling them jeans and Coca-Cola might have been more effective."

So what if the 'limits to development' listed by our three experts are not minor irritations, but part of a structural systemic change? What if the government of Vietnam were to decide that the human cost of development is too high? What if the people of Taiwan were to decide that the levels of air pollution, poisoned farmland, and the doubling of cancer rates are too high a price to pay for GDP growth? While Antoine van Agtmael commented (interview, above) that the environment is something that should be at the back of your mind when you invest, perhaps social and environmental issues should be at the front, - the political and economic landscape is moving towards placing these among the new survival imperatives.

The inevitable de-linking of 'development' and 'growth', through national and international politics, will have a profound effect. This is likely to be especially rapid in Asia where:

What changes might ensue from a reconceptualisation of development? Localisation is inevitable, and many large corporations have taken tentative steps down that road, giving local operations more autonomy. There will have to be a substantial shift, at least temporarily, in favour of sectors and projects providing infrastructure for people - basic housing, clean water etc. There will be more appreciation of the true cost (not necessarily quantifiable) of so-called externalities, which are rapidly becoming politically unacceptable. The pain in some industrial and insurance sectors from liability for past environmental damage is barely the beginning - as awareness of the broader implications of competition to externalise costs increases, the potential for claims across a much broader base of environmental and social damage is immense.

The 'Tiger' model cannot even be repeated across Asia, let alone transplanted elsewhere in the world. Not only are the disadvantages becoming more apparent but the necessary intervention would be subverted and punished by the markets. Much of this analysis has been theoretical, and its relevance broad. But the message is that Asia may turn out to be the catalyst for global change.

To return to Harry Truman, Wolfgang Sachs, Fellow of the Institute of Cultural Studies in Essen, Germany explains the fundamental assumption underlying the coining of the term 'underdeveloped': "... Truman conceived of the world as an economic arena where nations compete for a better position on the GNP scale. No matter what ideals inspired Kikuyus, Peruvians or Filipinos, Truman recognized them only as stragglers whose historical task was to participate in the development race and catch up with the lead runners. Consequently, it was the objective of development policy to bring all nations into the arena and enable them to run in the race."

The analogy is a good one - in such a race, 'catching up' inevitably means leaving someone else behind. An increasing number of Asians would rather not be running this particular race, as evidenced by (for example) the rising numbers of labour disputes across the region and, especially, the strength of their NGOs joining the forces for change in international politics. This process is nothing to fear - it is an enormous opportunity, but the survivors will not be those who cling to the mirage of the competitive, urbanised, industrialised Utopia so successfully sold to Asia. The message is to look not only at 'economic fundamentals' but to recognise and accept the situations in which the socio-economic, political and environmental realities finally speak louder than money.

Jon Ralls, November 1996

(c) 1997, Centaur Communications Ltd

![]()

Graphs:

Chart 1:

Chart 2:

![]()

Bibliography of quotations:

Jon Ralls and International Fund Strategies are grateful to those who contributed ideas and contacts. Comments or requests for further information are welcome by email.

![]()

• Top of Page • Back to IFS Intro • Home •