![]()

![]()

| Jon Ralls looks at issues raised by the global pensions

financing crisis and talks to SBC's Hans Ender and State Street's Bill Shipman.

(INTERNATIONAL FUND STRATEGIES, September

1996 |

|

|---|

![]()

There can be few topics as complex, all-embracing and deeply personal as provision for the elderly. Its financing affects individuals of all generations, national economies, distribution of income and wealth, and issues of democracy and corporate governance almost beyond imagining. Approaches are deeply affected by our fundamental beliefs about freedom and compassion, individual and social responsibility and the roles of government and free markets. And, above all else, it is an area in which all aspects are interdependent and even our most basic assumptions should be called into question. Small wonder that individuals and governments fail to bite the bullet and face the real issues.

But what are those issues? The World Bank talks of "Averting the Old Age Crisis", but what is the nature of this crisis? What solutions are on the table, and how are they influenced by the assumptions and perceptions of their proponents? This feature looks at two proposed solutions, one based on Chile's system, one on the table for the U.S., both involving the financial sector to provide a funded solution to financing retirement benefits. However, questioning some of the assumptions and objectives underlying such schemes could raise serious doubts about their long term effectiveness. In some spheres, they may even exacerbate the causes of the problems they seek to address.

|

The World Bank's 1994 Research Report "Averting the Old Age Crisis" will be familiar to many readers. The statistical information it contains is clear - birth rates are falling, life expectancy is rising and, throughout the world, there is an increasing ratio of old to young people. Further: "...old age security systems are in trouble world-wide. Informal community and family-based arrangements are weakening. And formal programs are beset by escalating costs that require high taxes and deter private sector growth -- while failing to protect the old. At the same time, many developing countries are on the verge of adopting the same programs that have spun out of control in middle and high-income countries."

But to call this "the old age crisis" is to make limiting assumptions and value-judgements - "the old age crisis" has been with millions of people for many years. The World Bank and others are addressing a financial crisis in our formal system of retirement provision, and trying to help other countries to avoid falling into the same trap. Looking at the problem in these terms simplifies it but, as we shall see, precludes discussion of many underlying problems.

The report does not ignore many of these issues: "More than half the world's old people are estimated to rely on informal and traditional arrangements for income security... Economic development weakens the informal arrangements... in industrial societies, people are more likely to withdraw from productive work, to live alone, and to depend on non-family sources of income in their old age." It cites five problems which are used to justify government intervention:

but points out that interventions have frequently led to inefficiencies and perverse redistribution to the rich. It does not go as far as to condemn such intervention - rather it raises some key policy issues to be considered:

In practice, the three most common financing and managerial arrangements are:

When it comes to policy choices, the report argues that old age security programs should be both an instrument of growth and a social safety net. They should help the old by facilitating shifting of income to later life, redistributing in favour of the lifetime poor, and providing insurance against particular risks. They should help the economy by minimising hidden costs (disincentives, fiscal burdens, evasion etc.), being 'sustainable' (see below), and being transparent to all participants and insulated from political manipulation.

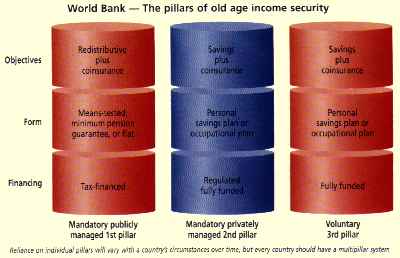

The Bank's solution is to adopt what are known as the "three pillars" (see diagram), already coexisting at varying levels in the systems of many countries and cites their success in Chile. Under this system, the public pillar should be modest, for example as part of a means-tested provision for the poor of all ages, or providing a minimum pension guarantee to a mandatory savings pillar. It could even provide a universal or employment-related benefit that coinsures a broader group.

The second mandatory pillar should be fully funded and privately managed which, by boosting capital accumulation and financial markets, should induce economic growth, making the first pillar easier to finance. The voluntary third pillar would provide additional protection for those who want more income and insurance in their old age. This system separates the redistribution and savings functions, but spreads the insurance function across all three pillars.

The World Bank's analysis does not ignore the fundamentals but, having raised key issues, takes them as given - as determinants not variables. Key decision-makers are proposing and implementing solutions to these and other problems with the very best of intentions, but on the basis of incomplete information, flawed models and excessively rigid assumptions. In the final part of this feature, some of these implicit assumptions are addressed, exposing some 'real issues' underlying the symptom of financial crisis. First, IFS put some of the issues to two influential industry figures, and asked them how their companies are tackling anticipated changes.

![]()

![]()

The Interviews: print copy includes interviews with:

| Selected Highlights of the Carter/Shipman plan for reforming U.S. Social Security |

|---|

|

![]()

![]()

Solutions based on conventional economic theories are beholden to the assumptions and limitations of those theories -- criticism of such solutions implies no judgement on their architects, but the emerging paradigm shift throws a different light on the benefits of global privatisation. |

The privatisation proposals put forward by the World Bank, the CATO Project and others recognise the scale of the financing problem, and make well-reasoned and well-intentioned attempts to solve it within the present system. However, even within current assumptions, these proposals have some worrying features.

Hazel Henderson, independent futurist and international consultant on sustainable development, believes that "privatization à la Chile would be a bonanza for private asset managers, but a potentially hazardous social experiment." She observes that, even if the ethics and skills of asset managers are universally impeccable, their activities fully transparent and accountable, and government oversight incorruptible, retirees will lose because many asset managers will under-perform. Although, on past records, even poor performance would be 'better than Social Security', this would no longer hold true. Henderson argues that it is in the nature of competition that retirees cannot all win, and that "additional trillions of dollars cascading into global markets, chasing too few good deals and investment opportunities will tend to lower average returns and/or push asset managers into riskier strategies to maintain yields."

- Hazel Henderson |

||||

This she attributes to a fundamental flaw in mainstream economics - the 'tragedy of the commons' - that if everybody tries to beat the system, the system breaks down. In her book, "Building a Win Win World", she puts forward strategies for "win-win" rules which restore the functionality of systems, by recognising and embedding common goals in regulatory and fiscal policy. Without such a new paradigm, the 'tragedy of the commons' will be repeated in market after global market with increasingly disastrous results, says Henderson.

The broader tools of systems analysis have been available for decades, but economists are only just discovering them. At present, under the banner of 'chaos theory', they are being used to try to beat the market, and being abused to argue that you cannot do so, and that government should therefore never intervene. Superimposed as they are on traditional linear economics, Henderson believes that such arguments have limited validity. Opened up to interdisciplinary approaches, systemic interactive models have a great deal more to say.

Applying such a broader approach to the 'old age crisis', it becomes clear that key interconnected factors have been taken as given and unalterable in almost every discussion and proposal. We are challenged to re-examine our understanding of such fundamentals as economic growth, development, concepts of wealth and welfare, and such sacred cows as the choice of our tax base. We can look at the interactions of corporate governance, political structures and assumptions about old age, freedom and human needs with a fresh eye, and apply the results to a more flexible model. Much of this is beyond the scope of this article, but some elements deserve further attention.

The World Bank report's sub-title is "Policies to protect the old and promote growth". It states that: "Everybody, old and young, depends on the current output of the economy to meet current consumption needs, so everybody is better off when the economy is growing -- and in trouble when it is not." But it also argues that "The challenge is to move towards formal systems of income maintenance without accelerating the decline in informal systems and without shifting more responsibility to government than it can handle."

There are two dichotomies here: Firstly that the process of growth-oriented development shifts people from informal care systems into the money economy. While this releases many (mainly women) from involuntary provision of care, there is a corresponding increase in the financial substitution for this care. Secondly, societal fragmentation itself increases consumption needs, as individuals seek to satisfy by consumption needs that were previously met outside the money economy.

'Development' and 'economic growth' can be seen as an accelerating spiral of dependency, with the financing crisis in social security as one symptom of a deeper malaise. Economic growth, as currently defined, is clearly unsustainable - numerous writers have shown that GNP is highly misleading. It includes, as positive contributions, activities such as pollution control that are purely "defensive" and it entirely fails to take account of human capital and resource depletion. Yet we build its pursuit into some of our most long-term policy decisions.

- Betty Friedan |

||||

The goalposts move again if we challenge what we mean by 'old'. Betty Friedan, in her book "The Fountain of Age", says "The assumption that we will all one day stop working, either by choice or because we are compelled to do so, has long been a fact of life in our society, which equates age with decline." As Bill Shipman pointed out, when many of our social security systems were put in place, life expectancy was very much lower. Retirees were likely to be in poorer health - more literally 'dependent'. Today the dependence of many retired people is largely a function of ageism in a labour market with no place for them.

|

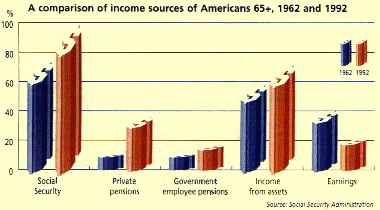

Underlying social and cultural assumptions militate against solutions within the present system. Friedan points out that a very large proportion of older people would very much like to work, so why has the proportion of 'seniors' income coming from earnings fallen over 30 years (see chart) while their health has improved? This has nothing to do with disincentives, just as it is quite unrealistic to help to solve the problem by raising the retirement age. People are finding that they are forced to take early retirement and become unemployable at 50 or younger.

There may be hidden costs to the economy of disincentives due to social security, but there is also the loss of this huge reservoir of experience and enthusiasm. We pursue higher labour productivity as a measure of economic efficiency, we tax employment and subsidise labour-saving technology and resource use, then find that we cannot sustain a huge 'inactive' population. Work by economists such as Ernst von Weizsacker suggests that a more rational choice of tax base that utilises disincentives instead of being limited by them could have highly beneficial systemic 'ripple effects'.

The danger is that the solutions being put forward to solve the financial crisis we now face will fail to address much deeper underlying problems. The World Bank argues that the choice of solution must be 'sustainable', and this is really the crux of the matter. What do they really mean by 'sustainable'? If the chosen solution is perceived as inequitable then, in the long term, it is not socially and politically sustainable. If it relies on, and contributes to economic forces and social trends that are themselves unsustainable, it is irrelevant that it appears to solve the current financial and demographic equations. We can no longer attempt to resolve these issues one crisis at a time.

Jon Ralls, November 1996

© 1996, Centaur Communications Ltd

![]()

(Discussions with and writings by a great many other individuals also contributed to the shaping of this feature.)

![]()

• Top of Page • Back to IFS Intro • Home •